In June 1969, a Time Magazine article garnered national attention when it brought to light the water quality conditions in Ohio: a river had literally caught fire.

Oil-soaked debris ignited after sparks, likely from a passing train, set the slick ablaze. Local media actually didn’t spend much time reporting on the fire. This was, after all, at least the 13th time a waterway had been set ablaze in Ohio alone, not to mention river fires in Philadelphia, Baltimore and other industrial cities. Time Magazine didn’t even run pictures of this specific fire. Instead, they used stock photos of another fire that happened in the same area in 1957.

But America in 1969 had had enough with dangerous rivers. At the national level, what would eventually become the Clean Water Act passed with broad bipartisan support in 1972. In fact, the law was so popular on both sides of the aisle that when President Richard Nixon eventually vetoed the bill, Congress overrode his veto.

Today, the quality of river water has improved markedly since the early 1970s, though critics say the red tape imposed through the Clean Water Act has become burdensome.

The Clean Water Act has not been altered much over the past 50 years, though how we interpret the act has recently changed dramatically. And water quality concerns continue to mount as studies have shown that some pollutants, such as PFAS, are a grave concern to public health and aren’t regulated by the Clean Water Act.

Limiting pollution, raising awareness

Though a Cuyahoga River fire near Cleveland helped to spark the Clean Water Act movement, arguably the law had an even greater effect on the Ohio River.

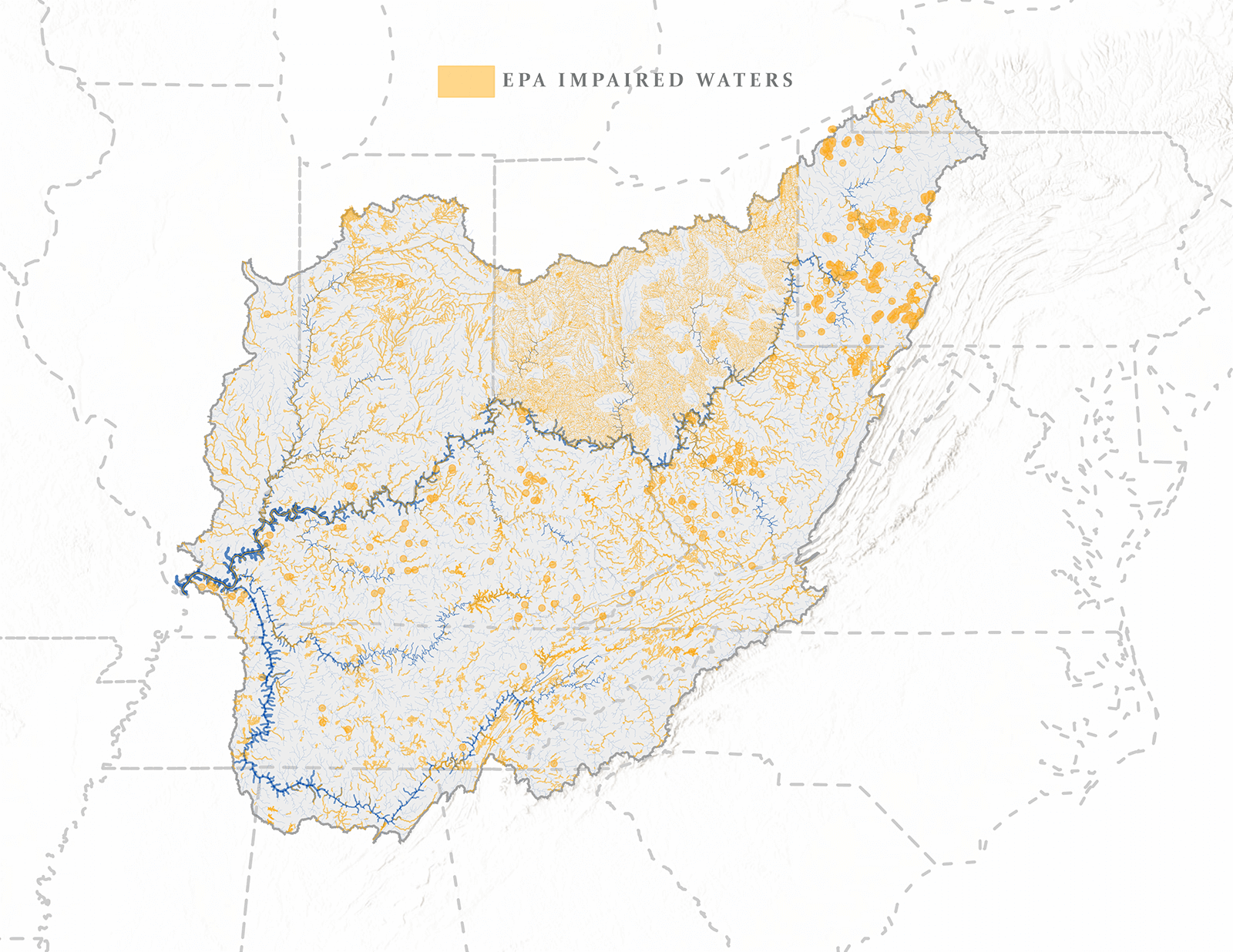

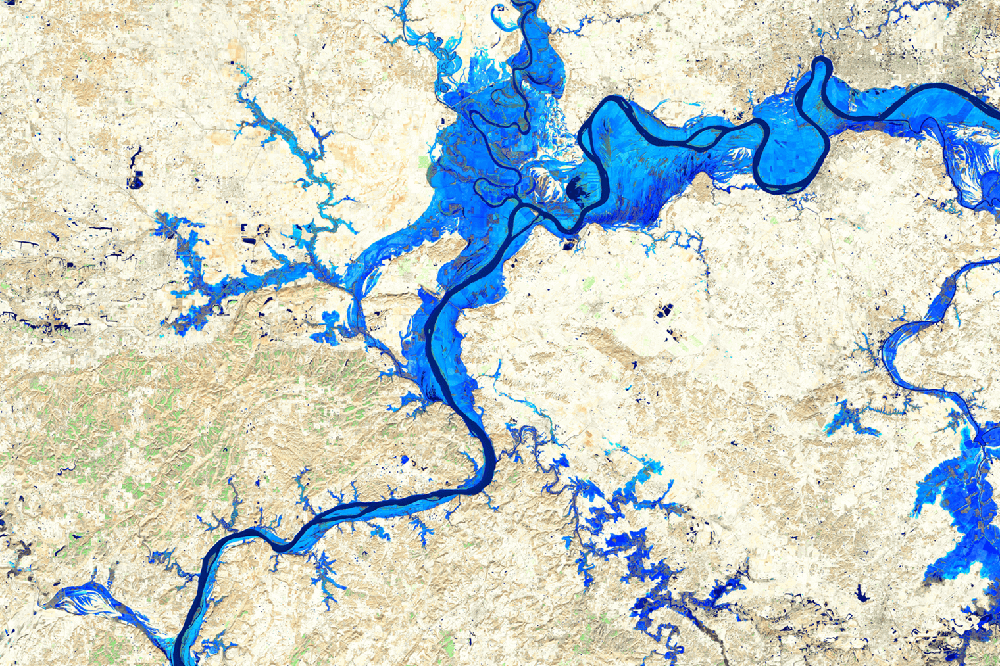

The Ohio drains the southern three-quarters of Ohio, as well as parts of 14 other states. A history of early industrialization, combined with legacy stormwater systems and heavy agricultural use, led to the Ohio River being named the “most polluted” river in the United States as recently as 2015.

Still, today the river is much cleaner than it was. Residents also have more access to water quality information: They can look up what contaminants their drinking water contains or if the Ohio River has tested positive for harmful bacteria.

The Clean Water Act [CWA] requires a permit for any regulated pollutants dumped into large bodies of water. Congress authorized the general framework to protect the quality of local waters and delegated its administration to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency [EPA] and the states. For example, the EPA publishes scientifically justified limits for various pollutants under the CWA. States can write standards for those pollutants that are at least as protective as federally recommended criteria or more strict.

For example, E. coli bacteria can’t exceed 126 colony-forming units of bacteria per 100 milliliters. The EPA recommended the standard first in 1986, based in part on studies of a sewage-contaminated Ohio River beach near Cincinnati where swimmers got sick. In that particular case, the median coliform density of the water registered 2,300 units of bacteria per 100 milliliters.

The CWA significantly reduced the amount of contaminants found in local streams, though even in 2019, the United States still has not complied with the pollution and quality goals it set for 1983.

Notably, the CWA exempted most agricultural uses from permit applications, so that farmers spraying fertilizer would not need to seek a permit to do so. Nutrient overload, however, is a “widespread and worsening problem,” according to EPA reports.

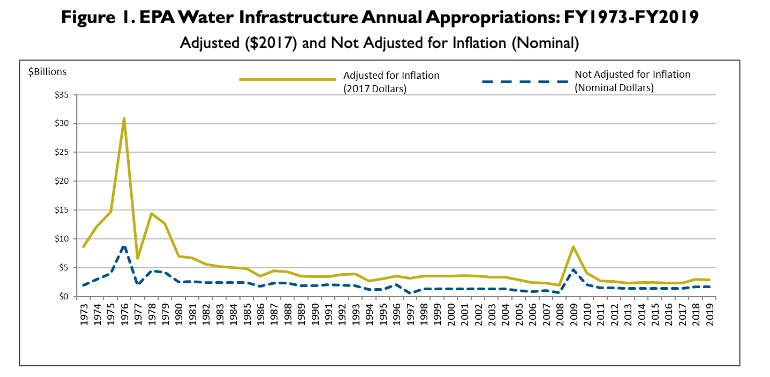

Since its inception, the CWA has instituted water quality standards for 150 different pollutants, such as toxic chemicals, nitrogen and pathogens. Altogether, the United States has spent about $129 billion on water infrastructure, including Clean Water Appropriations and water treatment plant financing.

Recent rollbacks

The Clean Water Act says it is a comprehensive program “for preventing, reducing, or eliminating the pollution of the navigable waters and ground waters and improving the sanitary condition of surface and underground waters.”

But what exactly are “navigable waters and ground waters?”

This question went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court in 2006, in Rapanos v. United States, when the Supreme Court had to decide whether four former Michigan wetlands counted as regulated bodies. They each laid near ditches or man-made drains that eventually emptied into navigable waters, though they weren’t directly adjacent to those rivers.

The court noted that the CWA made it illegal to dump without a permit into “navigable waters,” and the statute defines “navigable waters” as “the waters of the United States, including the territorial seas.”